Posts

The games of 2023

Monday, January 8, 2024

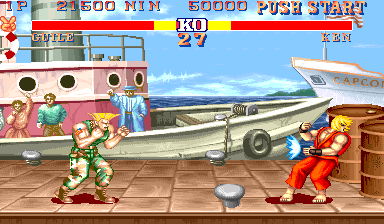

My games of 2023 are fighting games, largely Street Fighter 6. "Fighting game" describes a genre of video game in which players (usually two players) control avatars participating in a head-to-head martial duel. Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat are the towering franchises in the space—with mainstream sales figures and pop-culture recognizability—but the concept has been around long enough (Street Fighter II first came to arcades in 1991) to have inspired thousands of distinct iterations.

About a decade ago, I attempted to get into fighting games as a hobby, but found them too complex and reflex-dependent for me to play with any seriousness. It didn't help that in the 2010s, fighting games were still difficult to play over the Internet. Online gaming was extremely mainstream by then, but it took almost another ten years for network programming to catch up to the demands of the gameplay, in which each individual frame of a character's animation is gameplay relevant. (Other types of online games are more tolerant of various forms of fudging, where the game state is imperfectly shared between all the people playing and the results are more or less believable by the players when the system guesses at an outcome.) If you're interested in the technical facts, there's a fun explainer about fighting game "netcode" on Ars Technica: "Explaining how fighting games use delay-based and rollback netcode."

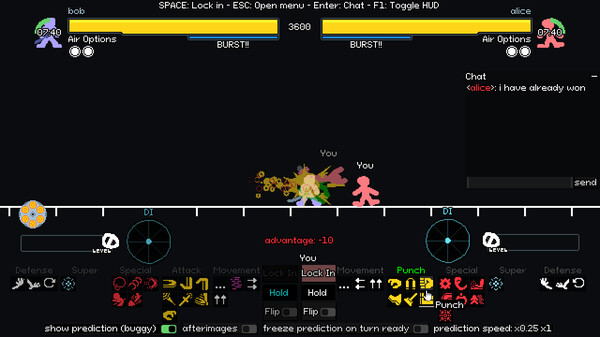

Nonetheless, I continued to dabble in the intervening decade, especially when clever game designers sought to make the fighting game experience more accessible while borrowing something interesting from the underlying gameplay design. The "fighting game offshoot" niche was abuzz in early in 2023, when a solo developer released a turn-based fighting game called Your Only Move Is Hustle (a.k.a. YOMI Hustle) after three frenzied months of development, baking in all the complexity of a fighting game while also making it time-agnostic. It's a two-player, head-to-head game in which you and your opponent pick moves in secret, and once both players lock in, your respective stick figure characters perform all manner of slick action movie animations. Punches, kicks, blocks, acrobatics—all the buildup and catharsis of action movie choreography in a $5 video video game.

I played YOMI Hustle intensively for a couple of months, egged on by the fact that a small handful of the game's fans were showing up to watch my very occasional Twitch stream. During one of those sessions, a viewer prompted me to try one of the first modern fighting games with excellent netcode, Guilty Gear -Strive-. I wasn't sold, but I couldn't shake the feeling that it would at least be an interesting failure, so I did exactly that and tumbled headlong into the niche of fighting games.

I was rewarded with a deep collection of community-built resources for Guilty Gear—players had documented how everything worked and what to learn in order to improve. I was learning combos, I was diving into the intense lingo. ("That's a setplay character; that's a good option if you want oki; if your opponents starts to tech you should shimmy.") I bought not one, but two fighting games-specific controllers, and I was playing in ranked matches where you gain points for winning and lose points for losing. I was trying in a dedicated way to become a better player.

That experience intensified even more when Street Fighter 6 came out a few months later, the latest entry in the long-running franchise (and a pop culture touchstone for lots of today's middle-aged, game-playing people). It surfaced a long-forgotten memory of visiting a corner store with my older cousins, putting my quarter on the cabinet, and eventually playing a game of Street Fighter II amidst a crowd of rowdy, shouting teenagers. SF6 has superb mechanics, it's a technical marvel, and the character designs this time around have been fun. It's also quite important to me that the scene is mature and inclusive—the majority refuses to tolerate the toxic behaviors somewhat common to other competitive games.

And so, fighting games are my Game of the Year. In 2023, I played more than a dozen games in the genre and had an incredible time with all of them. Sometimes I played "seriously" with an eye towards dedicated improvement, and many I've played to simply admire the art and design.

Playtime isn't everything, but I think it shows the extent of my capture; that the genre is working such comprehensive magic that I've chased the experience across many games:

- Street Fighter 6 at 250 hours

- Your Only Move Is Hustle at 40 hours

- Granblue Fantasy Versus Rising at 35 hours

- Guilty Gear -Strive- at 60 hours

...and even more that represent plenty of time in aggregate: Samurai Shodown (2019), King of Fighters XV, Pocket Bravery, Cyberbots, Soulcalibur VI, and throwing all the way back to Street Fighter II: Champion Edition (for which I entered a tournament and didn't come in last).

creative accountability, mini mastering experiment

Tuesday, August 2, 2022

I joined a Bitwig Discord, and the conversation at the time was about mastering. I watched the recommended YouTube videos and wishlisted some chunky books on my way down the rabbit hole, and this project reflects a loose attempt at working with some of those ideas.

To put it in my own words, I'd say that mastering is a late-in-the-production-process set of activities to prepare the track for modern consumption. I didn't really expect to touch this topic at all—I'm having enough trouble composing/arranging/performing something interesting—and yet, part of the "gap" between what I'm making and what I'd like to hear feels like it could be bridged by mixing/mastering techniques. To describe the situation really simply, the recordings I'm producing feel too quiet and pretty muddy, and this arcane skillset might help me climb out of the goop.

I configured a big-sounding Polysynth device and tapped out a basic drum pattern, and then used EQs, saturators, compressors, and the Bitwig mixing view to try and fill the spectrum and make it loud.

I don't let my channels clip—a habit from bygone days as a DJ on various kinds of analog gear. But my very loose understanding is that what looks like "clipping" matters less in an all-digital, single-DAW workflow because the underlying mathematics permit the proper handling of audio signals that exceed limitations in all other contexts. To quote the first Google result for "gain staging": "We’ve demonstrated that in the domain of floating-point, you can push above 0 dBFS and not harm the signal, so long as you dip back down on the track’s corresponding destination."

[LUFS LUFS LUFS]

So, here's my first attempt. It was measuring in Bitwig at -0.2 dB and (at around -16 LUFS if I remember correctly):

And here's an attempt that was absolutely clipping in Bitwig, but had a "true peak max" of -0.2 dB as measured by TBProAudio's dpMeter5 (at like -11 LUFS):

creative accountability, malihini mele loop

Wednesday, July 27, 2022

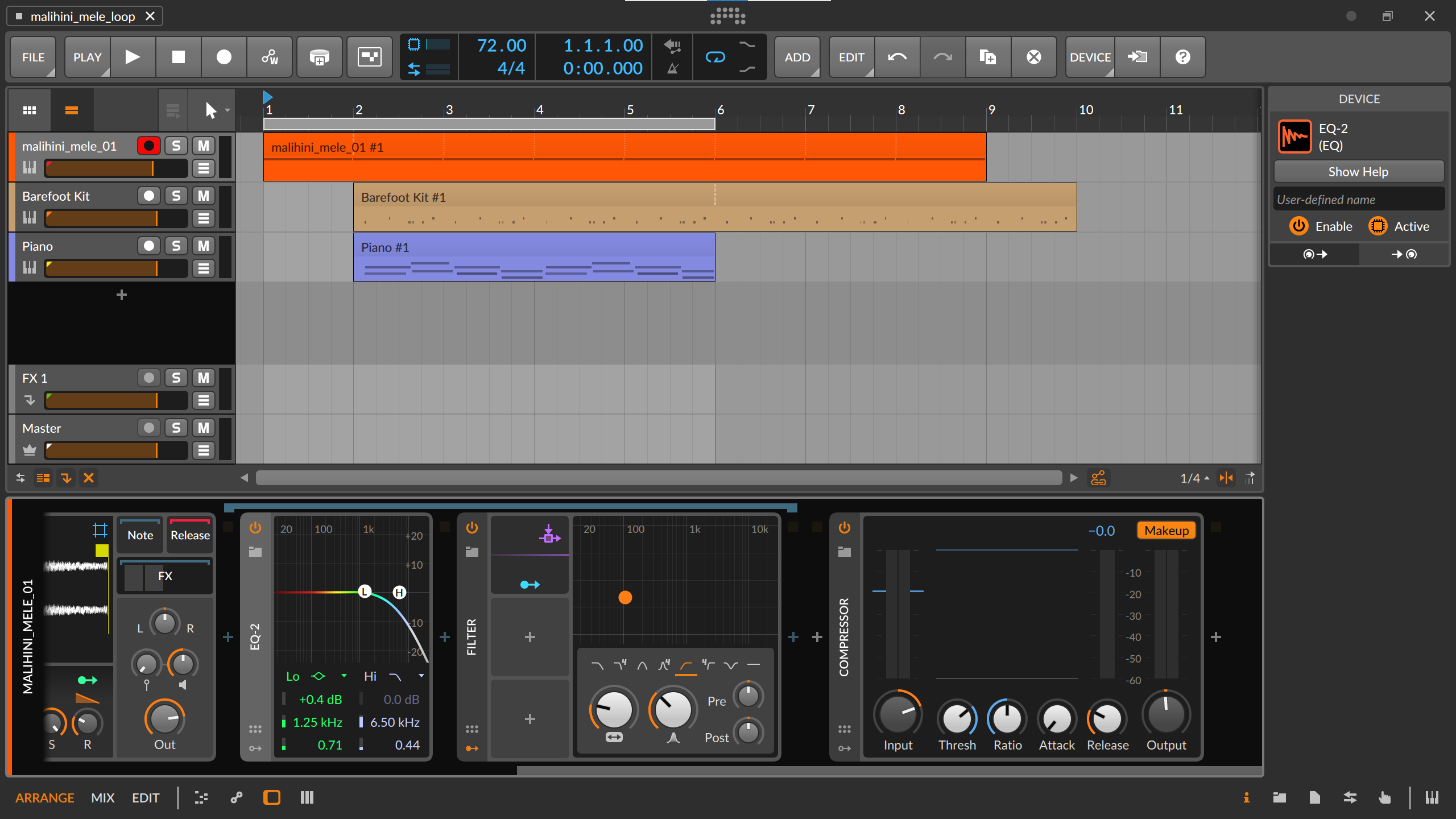

For this sketch, I went back to a loop-driven project after watching a neat YouTube video by Polarity about how to more reliably timestretch clips in Bitwig's sampler device. It was the advice missing from my last attempt at working from loops, and the technique helped this attempt feel much better:

I worked on this hours after returning from a long trip to Kauai, so virtually digging through crates of hapa haole songs was a way to give voice to my wistfulness.

Activities that seemed to make a difference:

- I did a better job of chopping up the sample for use as a loop

- I used the Ramp device on the sampler as advised by the polarity video

- I spent time trying various mixing techniques to give each track more space across the spectrum

I was absolutely attempting a "lo-fi beats to miss your vacation to" kind of thing. Evaluating the project after the fact, I can tell that I wanted to "validate" the work on the sample by having it be very present, but I think I should have at least tried EQing the sample down to more of an AM radio feel. I suspect it would sound better overall and still stand out.

creative accountability, pushing notes

Wednesday, July 20, 2022

Most of my time at the keyboard today was spent on piano-playing drills, but I did manage to load up "deep experiment" briefly to rework the chord progression once again. I ended up largely undoing what turned out to be shoddy work at the end of my last session with it. By "shoddy work," I mean that I had erred in identifying the 7th intervals for the chords—so the chords were simply wrong, and after fixing them, the inversions sounded more chaotic and didn't really provide the cohesiveness I thought was there.

I returned the chords to their simple forms and shuffled the progression around to a better-sounding-at-this-time iv - v - III - i (was previously III - iv - v - i). It feels a little like a bridge part, so I feel compelled to revisit it again later—but I'm left again with the feeling that I'm in a very naive place with this effort, and a little doubtful that I can "experiment" my way into something compelling.

I tried to read more about scale degrees and chord functions, but the advice I've found so far seems either too simple (like the introductory guidance about 2-5-1) or too far ahead of where I am now (I found what seemed like undergrad-level academic material describing the different functions of the third scale degree in different keys).

creative accountability, a return to deep experiment

Sunday, July 17, 2022

My kid learned that I've been trying to make music and has adorably been asking to hear the recordings. "Deep experiment" was one she liked, and upon learning that there were two versions—a creative stub, and then what I considered to be a more evolved version—she told me that the stub version was better, and my partner even agreed. So I returned to the stub version and tried to iterate from it in deep-experiment-1-2-2022-07-17-2346.mp3:

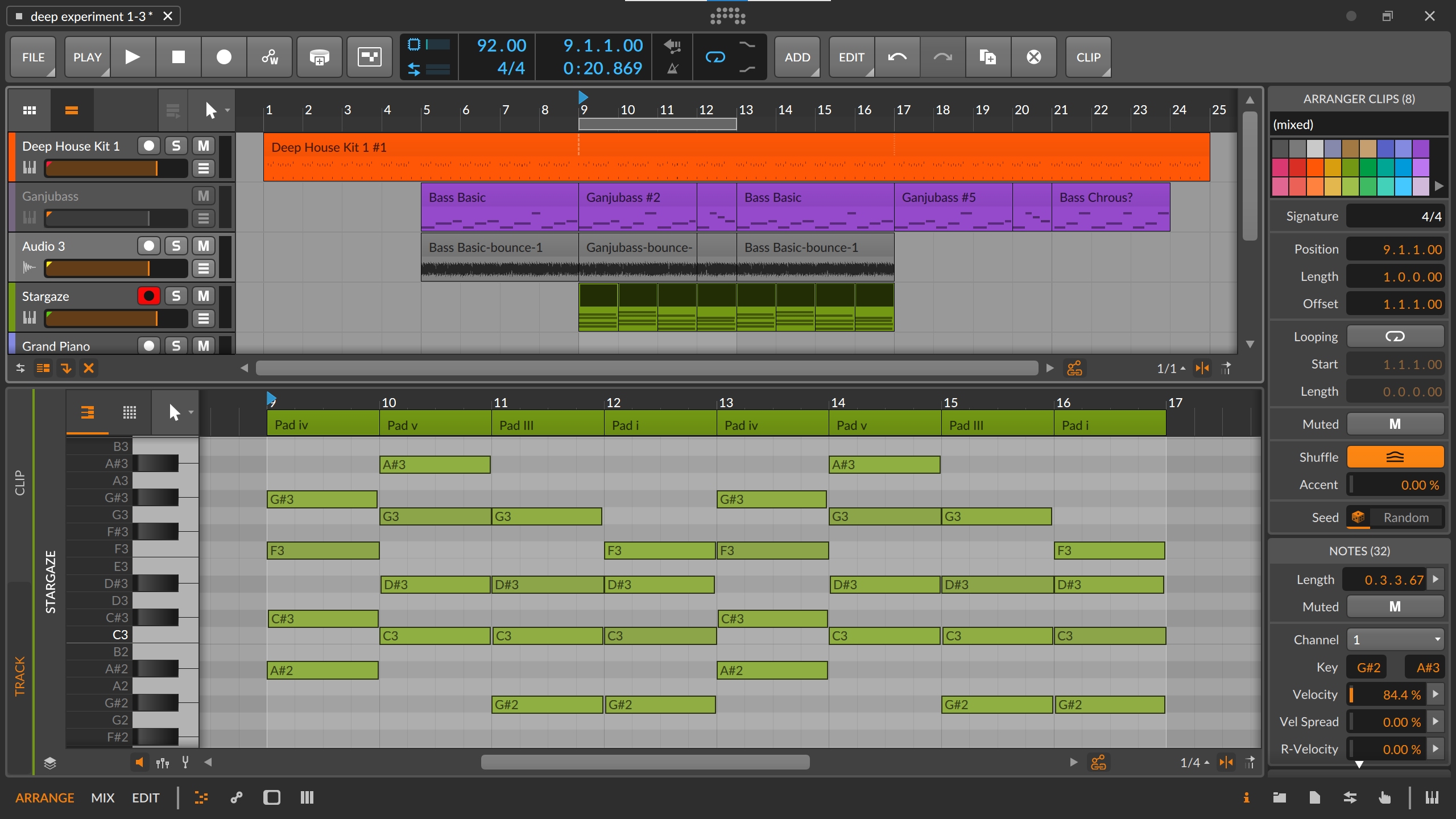

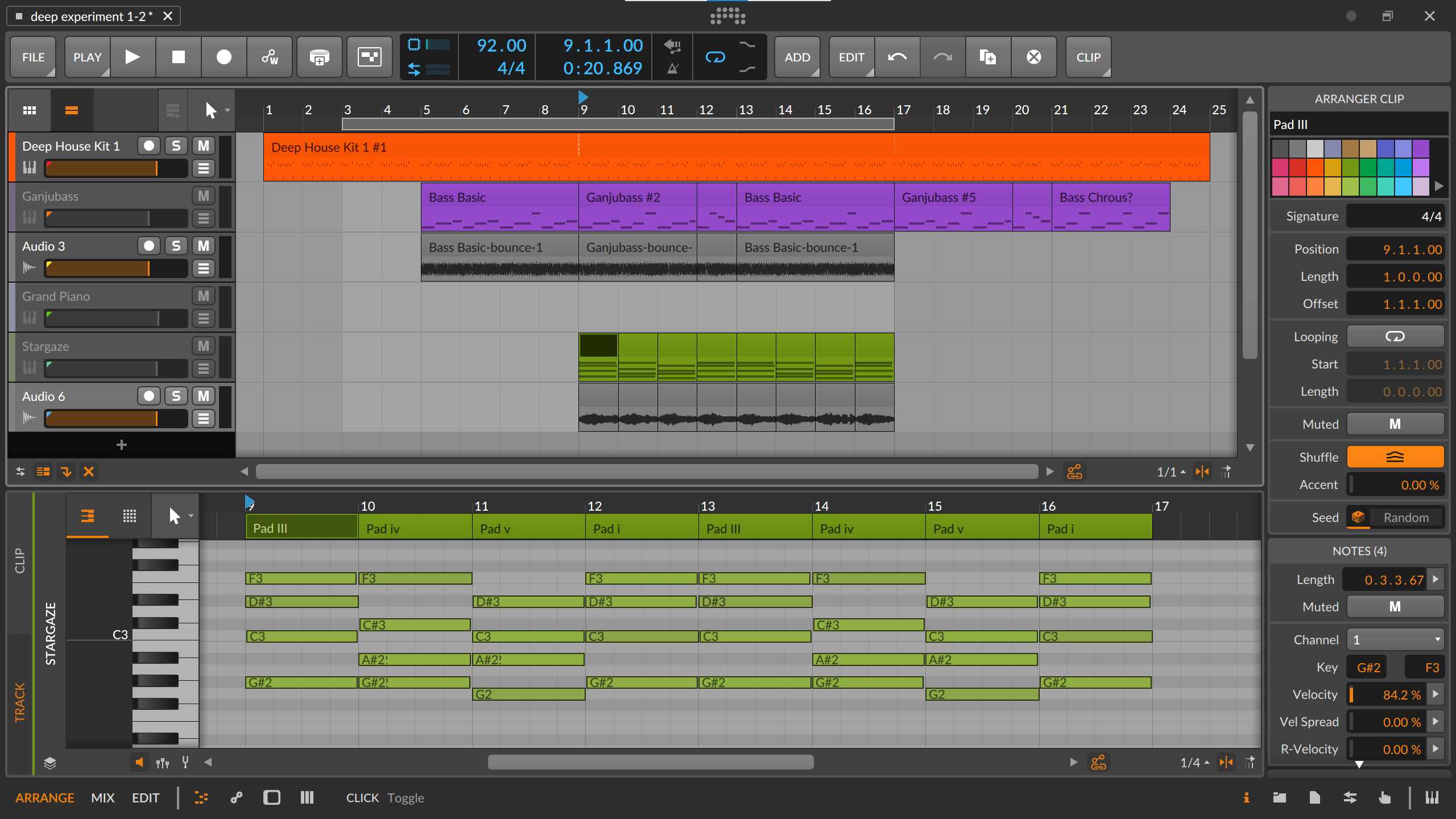

And here's a screenshot of Bitwig around the time of exporting the audio:

They preferred the bassline in the original deep experiment, so I returned to it. It was a sequence of F - G - C, and with that established, I figured I could try writing in F minor instead of F major. This time around, I did more homework—I wrote out all the notes of the scale and mapped out the scale's triad chords to give me a better map of what things to try. I wanted to evolve the bassline and ended up with more variation, mostly F - G - G# (darker!), with some F - G - C sprinkled in (dramatic!), and a fun F - F - D#- C# in the 8th bar. (I think of it like a little drum fill, but I suspect that's both (a) too soon for a drum fill and (b) not how other musicians think about their parts? Anyway...)

The chord progression and instrumentation in the first version of deep experiment was powerfully boring, and while folks in my family liked deep experiment 1 better, no one said that they liked the 2-5-1 pads, so that's where I started tinkering. The first chord progression I noodled out was a iv - v - VII - VI, and while I liked it, the scale mapping I wrote out made it more clear that this progression wasn't working alongside the bassline notes.

Attempting to work more with the basssline notes brought me to III - iv - v - i instead, which felt more stable. I did a lot of noodling to hear the chords in sequence, but my actual piano playing still sucks—so when the time came to record, I tracked the III chord, and then copied/adjusted the notes of the triad into new chords to make up the remainder of the progression. (Tracking the initial chord has the useful property of lending human unevenness to the played notes, so I still think it's better than simply drawing the notes into the chart.)

It sounded reasonable at this point, but I became much happier with it after playing with some inversions―with the intent of having the chord tones living closer to one another—and adding 7ths. But, I may have overdone it. While it did make for a more cohesive sound, it was also more flat and samey. (And I just noticed in reviewing the Bitwig screenshot that the manipulations I did on the i-chord ended up producing the same notes as the starting III-chord! No wonder it sounded same-y.) But now that I've done what feels like a stabilizing exercise to find out what musical ideas are at the core of this song, I think I'm in a good spot to revisit the composition to add more expression.

creative accountability, deep experiment 2

Saturday, July 16, 2022

Here's deep-experiment-2-2022-07-16-0011.mp3, an attempted successor to deep experiment 1:

I felt that the Supersoft Pad and the 2-5-1 chord progression didn't work, and so most of the work here involved trying to improve that. I went with a synth instead of a pad and noodled out a new v - IV - i - ii chord progression. Then, feeling a little nostalgic for the Supersoft Pad, I used a layering technique to drive the Supersoft Pad using the notes of the string part.

This felt like a meaningful evolution of the prior ideas, and I was pretty happy with what came together.

creative accountability, deep experiment 1

Friday, July 15, 2022

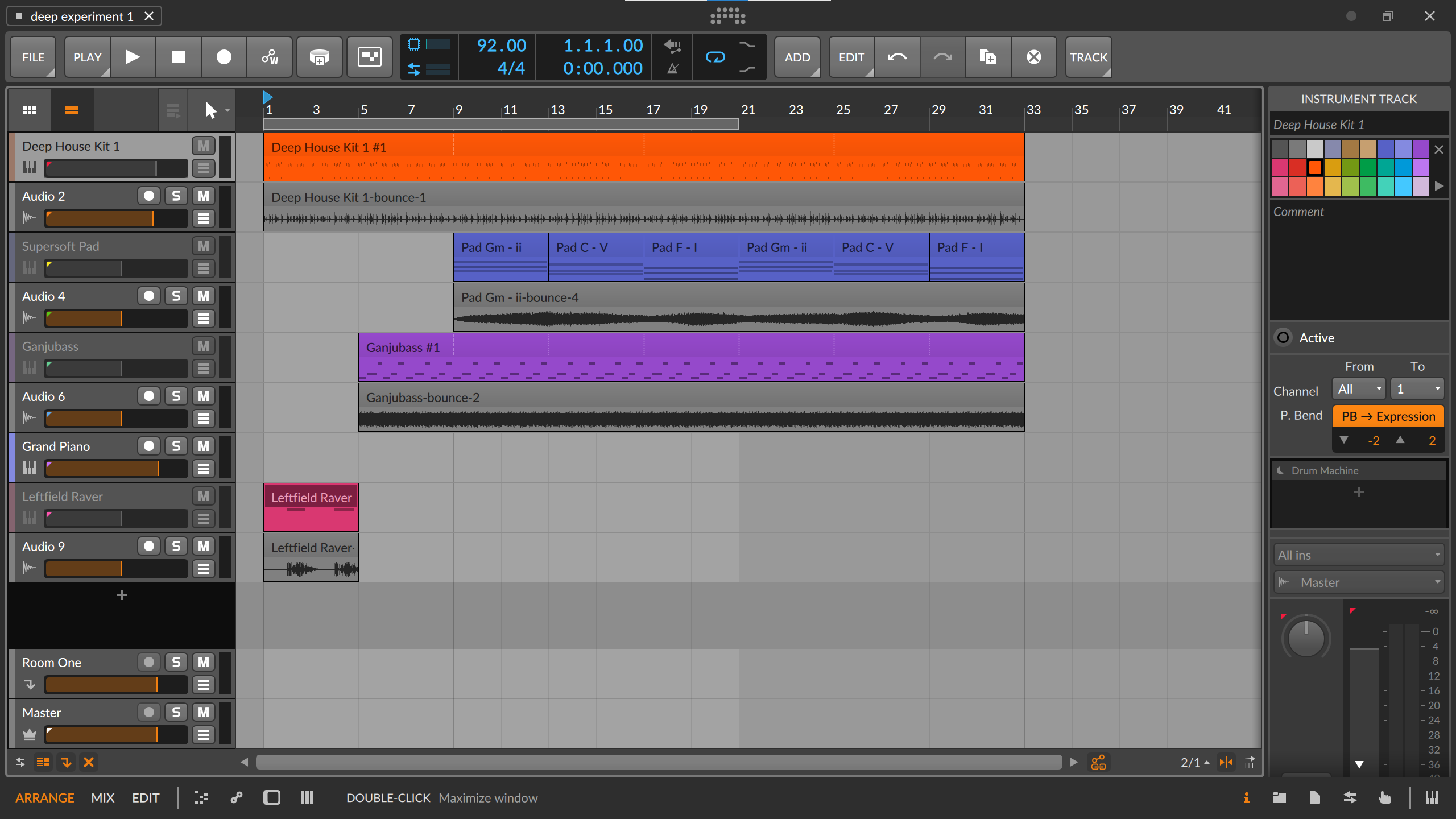

Here's deep-experiment-1-2022-07-15-0022.mp3:

It started with the Deep House Kit #1 and some play on the Oxygen Pro 25's really nice drum pads. With "organic house" still top of mind—see creative accountability, organic house from about two weeks prior—I tested out the kit's percussion sounds and was pleased to hear some woodblock-sounding samples, and ended up tapping out a pattern that felt natural. I knew I was making some kind of deep house/organic house track, so I set the typical 4/4 kick pattern.

Next, came the arpeggiated-esque bassline—see creative accountability, aka clouds)—another thematic approach that's been top-of-mind. Constructing the instrument was the most intricate part—it's the "Ganjubass" Polysynth preset with Note Repeater and Quantize devices added to transform played notes into a repeating series of 1/16th notes (if I hold the F key for a bar, it will sound like I pressed F 16 times). The notes were just noodled out; they sounded neat together.

In the past, I've regularly been able to get this far in producing something, but I've rarely been able to go any further. Until recently, I haven't had the time or training to know what to try next. But my instinct was to try to layer in a pad sound; the wide, sweeping tones that create a lot of size and momentum in the deep house/organic house compositions that have been serving as inspiration.

My naive take: this is a tough step because pad sounds are pretty subtle—as far as I can tell, the instrumentation is usually somewhat understated. If I were to dive way in over my head with an orchestra analogy, it's more strings than brass, and it means that it's hard to pick an instrument. Here, I picked something called "Supersoft Pad" knowing that I wanted it to take its time, though I think it's more forward than I really intended. I imagine if this project were to continue, I'd end up putting it through a low-pass filter of some kind to make room for some kind of lead instrument.

Unfortunately, I really didn't know what to do with the chord progression itself. I've been watching a lot of introductory piano, basic music theory and composition YouTube videos, and recently stumbled into 2-5-1-land—so an extremely rudimentary version of that is what's here, in the key of F major. To its credit, it sounds "complete," but it's not at all interesting.

The "Leftfield Raver" stabs at the beginning were a short attempt to find a lead instrument. It seemed like a dead end, but my affection for the instrument itself led me to try an early dusting for flavor only. In retrospect, I think it's too noisy and similar to the bass instrument.

creative accountability, in my paradise

Wednesday, July 13, 2022

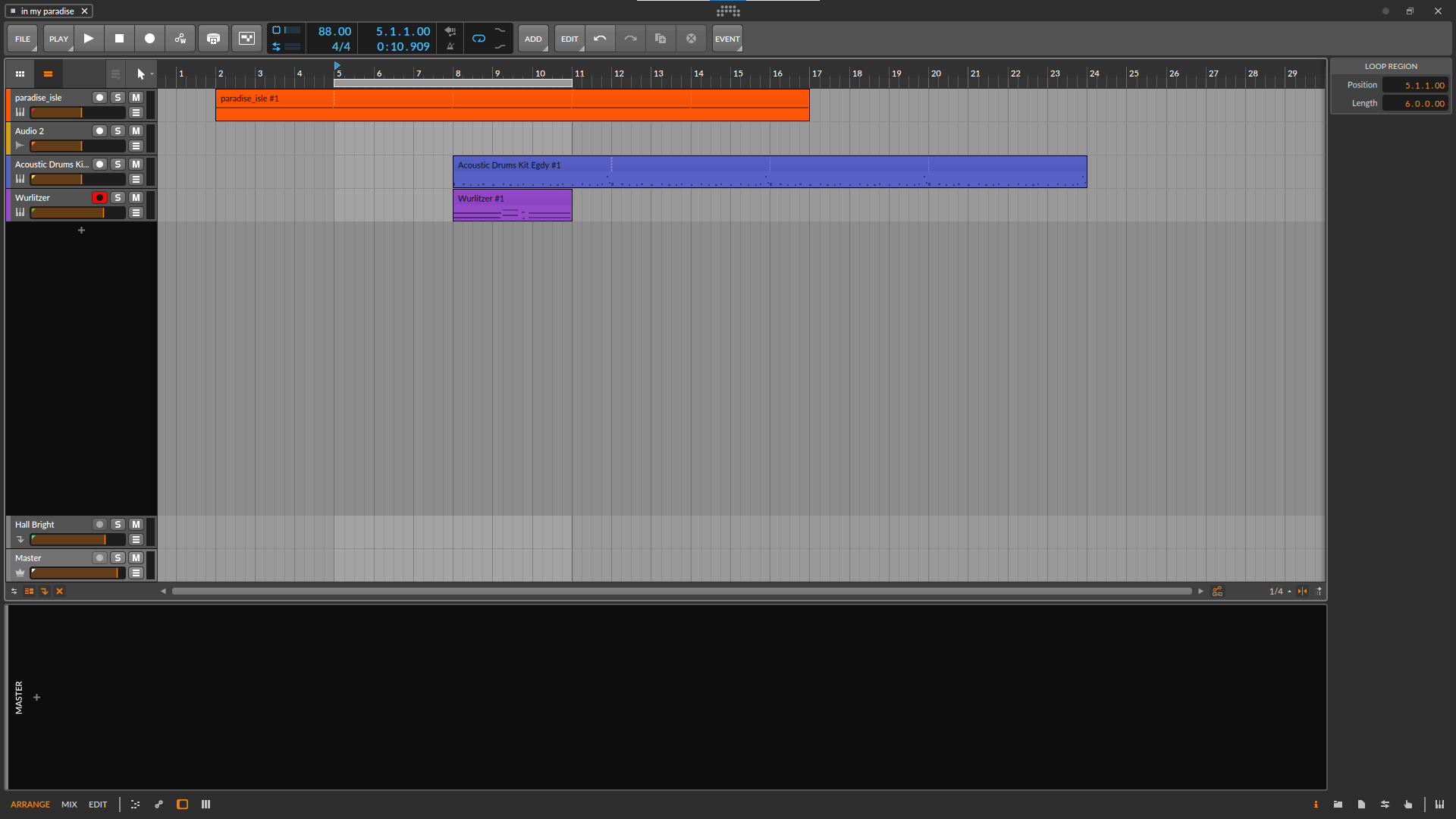

I've been shying away from samples—they seem hard to work with—but after being inspired by videos about Bitwig's Sampler instrument, I noodled together in-my-paradise-2022-07-13-2319.mp3:

This was a good exercise, but I'm not too happy with the final product itself. Finding good source material is an essential part of the process and can be incredibly time consuming. Even in the best of circumstances, I'm short on time, and in this case I was rushing to try something instead of taking the time to find something more ideal or taking the time to shape the sample into something that works better. That said, the process was fun: I went to archive.org and looked through their 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings, and eventually found Bing Crosby favorite hawaiian songs Volume One. Track 9 is "Paradise Isle" and I found something likable to try.

I tried to accompany the sample with drums and a melody on the Wurlitzer instrument, but all told it feels quite off kilter. I think I'll have to either find better samples or learn better techniques for noise correction, time stretching, pitch, and slicing them to be played in a more MPC-like way.

creative accountability, beep_it_like_its_fraught

Thursday, July 7, 2022

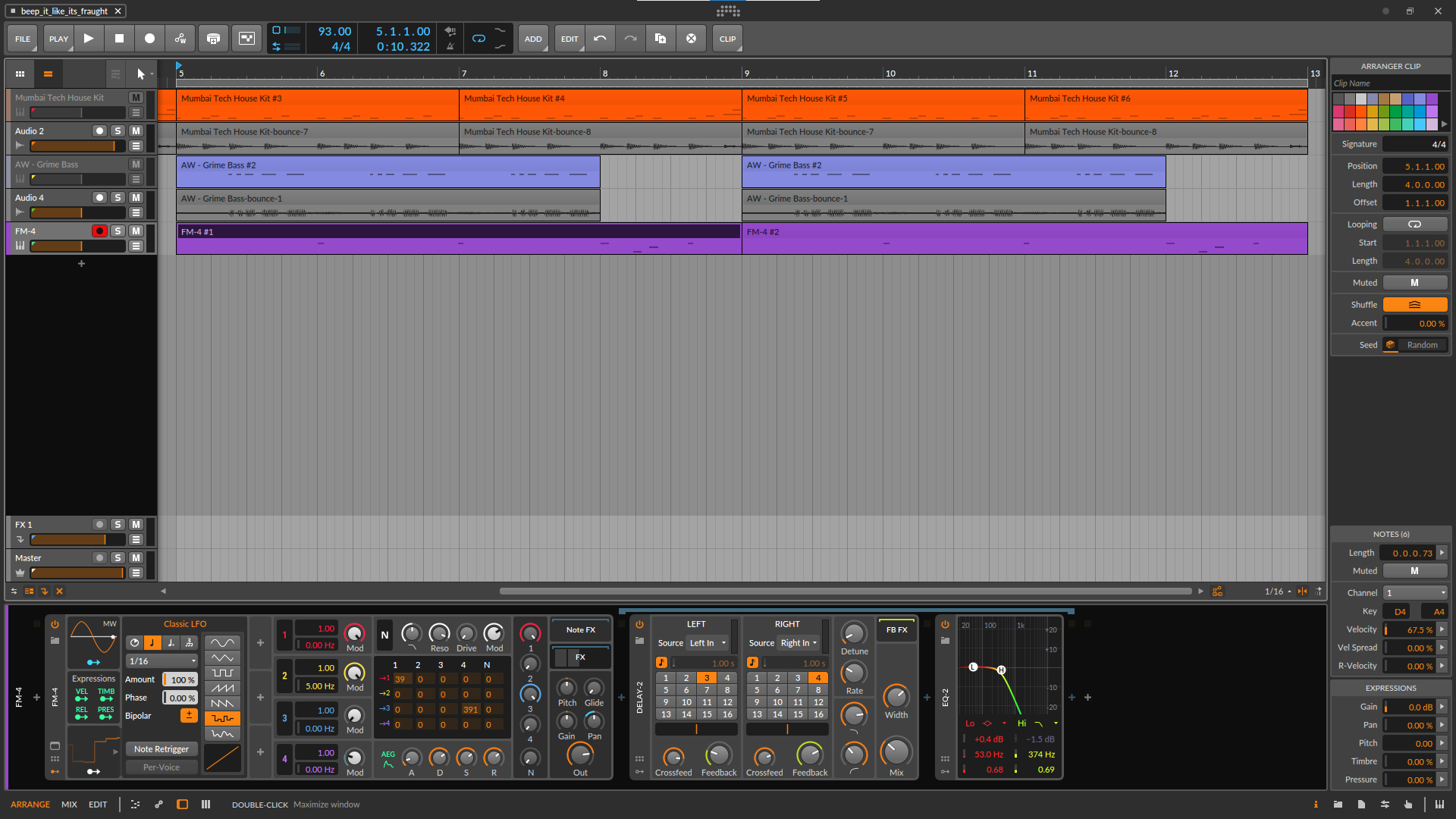

When a drum kit feels punchy, yet minimal, I absolutely cannot keep from playing a pattern like "Drop It Like It's Hot," and so here's beep-it-like-its-fraught-2022-07-07-2301.mp3:

I configured the FM-4 instrument that's providing the beeps.

creative accountability, aka clouds

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

Here is arpeggiated-bassline-aka-clouds-2022-07-06-0902.mp3:

A day or two before working on this, I heard Supernature - Somewhere In Time and took the note "arpeggiated bassline," so that was clearly part of the inspiration for this bit of noodling. This piece has more songlike structure compared to most of the bits I've made prior, primarily in the form of introductory drum bars and more variety in the lead melody.

I've been trying to take inspiration from the dramatic clouds on the island. They sit low in the sky, move quickly, and tell vivid stories with their shapes. I don't think that comes through whatsoever in this composition, but as I tell my kids: trying is important.